Ecovillages are small, intentional communities where the residents have chosen to focus on reducing their environmental impact and developing more sustainable lifestyles. They engage in grassroots innovation and can play an important role in the transition to a more sustainable society. However, it is important to consider not just the innovations, but the way those innovations diffuse into, and are adopted by, the larger society. By modeling a high quality of life while achieving a low environmental impact, ecovillages can point the way toward sustainable consumption practices.

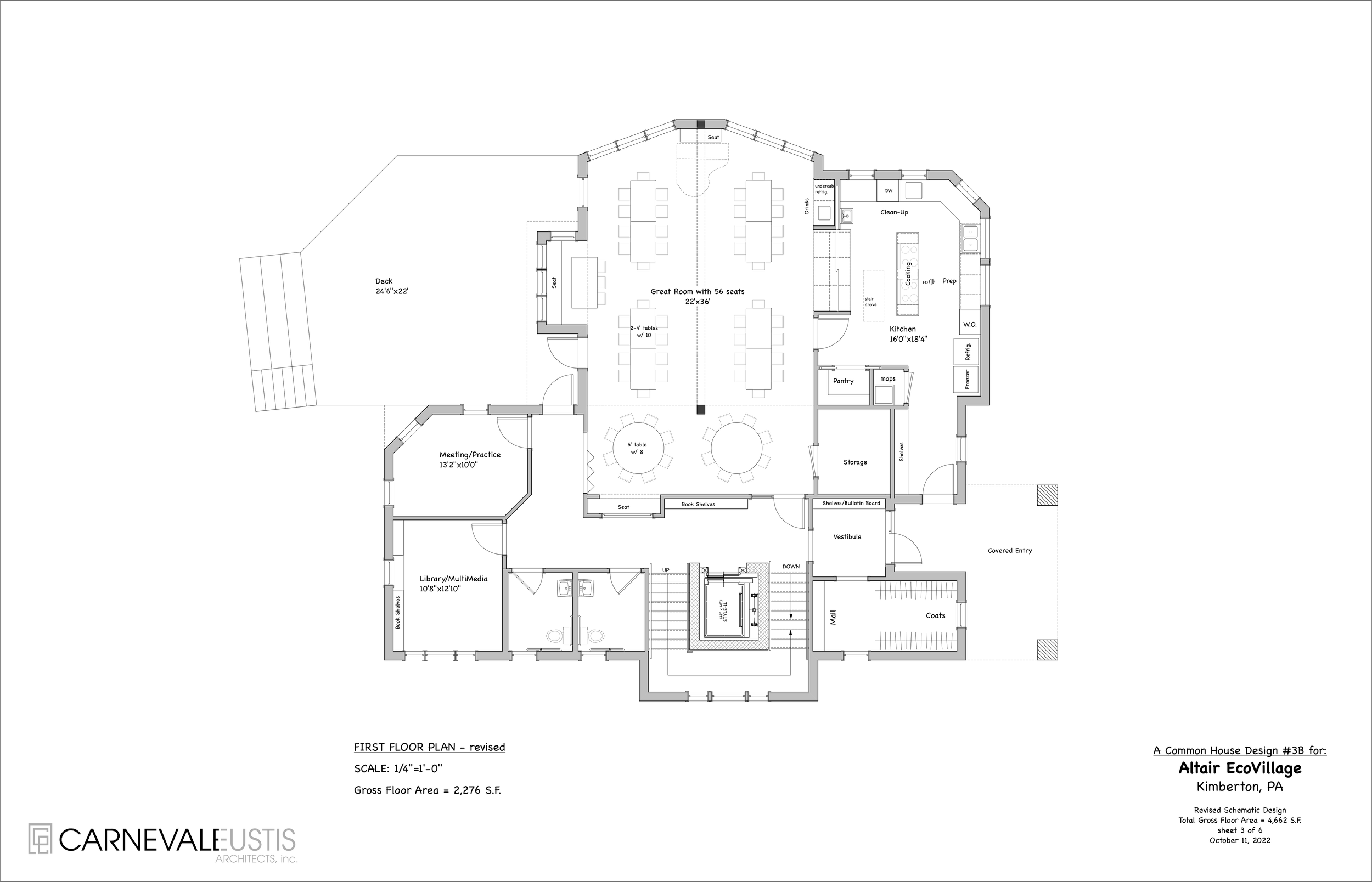

For Altair EcoVillage, we plan to address our environmental impact by addressing four areas of activity: home energy use, transportation energy use, food consumption, and waste disposal. At Altair, our homes will be powered with electricity generated by solar panels above the carports. Though we are required by the township ordnance to supply 50% of our own power, we plan to generate enough to meet all of our needs. For reducing transportation energy use, we are currently working on a car sharing program and already have a small fleet of electric vehicles that can be shared by the members. As far as food consumption, we will have a community garden and be able to host meals in our common house. However, as we have three local CSA’s (Community Supported Agricultural gardens) and a well-established whole foods store a block from our site, we can rest assured that any money spent will go to support our local commerce. We plan to establish a robust recycle and compost program. As an ecovillage, our objective is to find a way to maintain a high quality of life while decreasing consumption and environmental impact.

Another way Altair is hoping to be on the cutting edge of sustainable stewardship of the land is to fulfill the requirement in the township ordinance to achieve at least a silver rating from the US Green Building Council for the SITES initiative, which addresses practically all aspects of sustainability from responsible soil management practices to using local labor and materials to build the project. The members of Altair are committed to monitor and maintain the program for ten years.

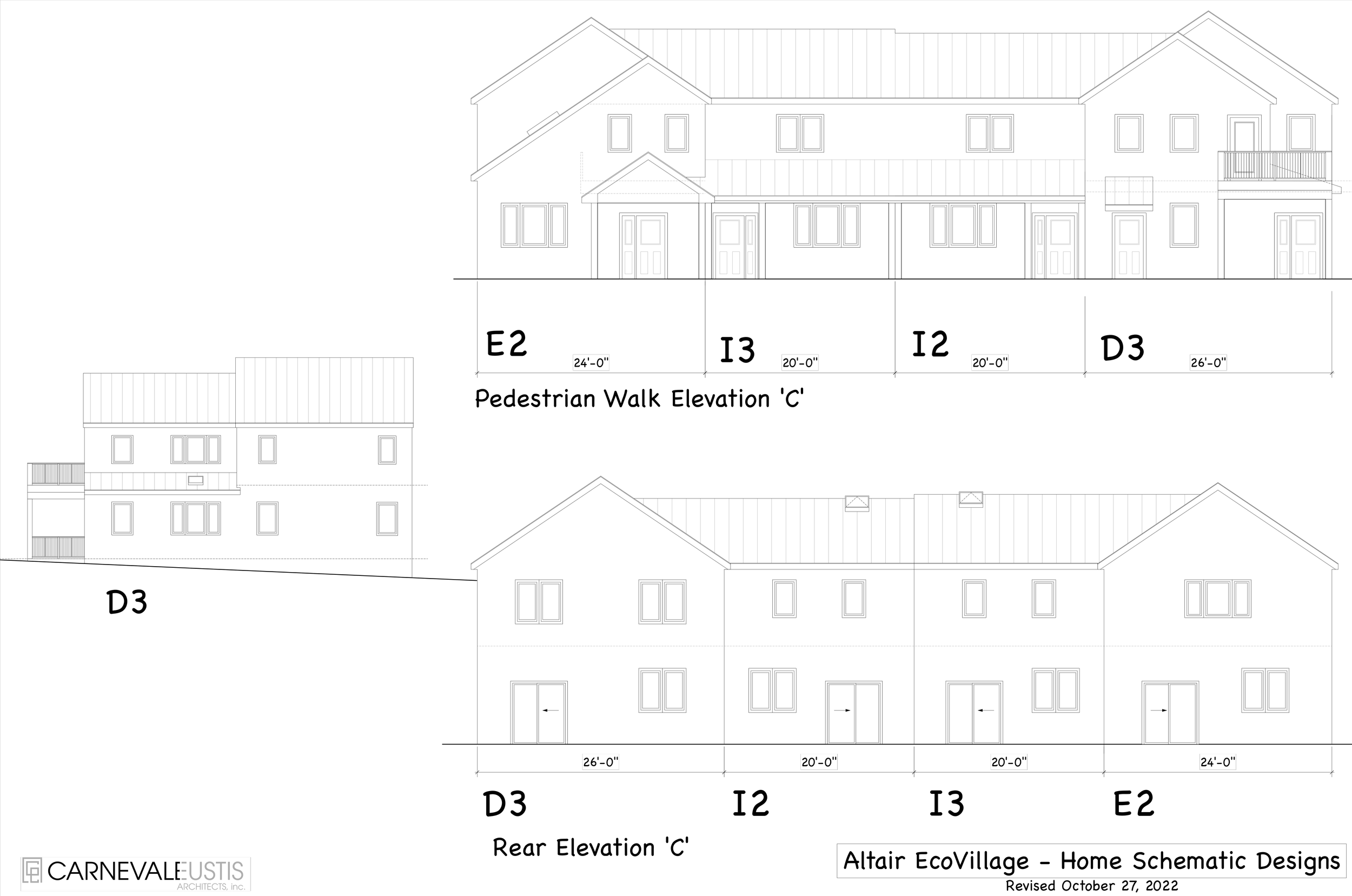

The Passive House building certification, well beyond the township ordinance, is another measurable effort to reduce significantly the heating and cooling loads for the homes while using non-toxic materials, filtering outside air, and providing the healthiest homes possible. By purchasing factory-built panels, we reduce the construction timeline and assure quality control.

Sustainable consumption (defined as “patterns of consumption that satisfy basic needs”) is required to offer humans the freedom to develop their potential without compromising the Earth’s carrying capacity. Significant changes in consumption patterns are required. Intentional communities provide one resource for investigating alternative habits, ideals, and norms around consumption. These can provide useful strategies for addressing both the conceptual and technical issues.

By modeling a high quality of life while achieving a low environmental impact, Altair EcoVillage can point the way and be an example of sustainable consumption practices.